.

In 1890, the boostering land owners of Vancouver and New Westminster — backed by their respective mayors and financial elites — decided it had become necessary to link the two cities by means of an electric interurban railroad. One contemporary observer later confided that “there was a strong suspicion in many minds” that an effort to enhance real estate values was a more important factor to the original investors than was the improvement in communications. No doubt this was true, but, of course, this was a period when the conjoining of public need and private profit was a vital element in the breaking of new ground. After some perhaps shady real estate deals were completed, Vancouver’s usual suspects – Israel Powell and David Oppenheimer and Charles Dupont – ended up with options on the Hastings Mill land. A. R. Ross, Walter Graveley and others were also involved. And it was this coalition of shifting owners along with British money that took on the interurban project. i

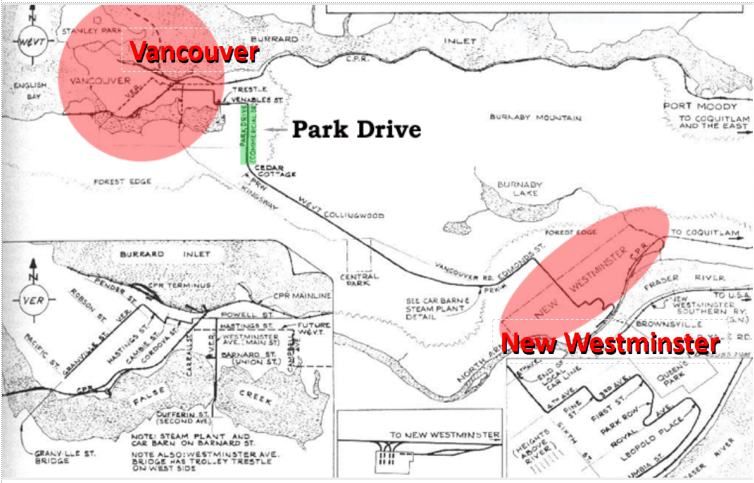

It may well have been the existence of the original park trail that encouraged these promoters to push their rails through Grandview in 1891. The company engineers were busy from June 1890 surveying a variety of lines between the two cities. In August the following year, City Council finally approved the route into Vancouver from Cedar Cottage. The route would follow Park Drive, turning west on Venables Street, onto Campbell Avenue and thence along Hastings Street to the terminus at Carrall Street.ii

Because City Council wanted no dispute with the Vancouver Electric Railway and Light Company (VER&LCo) which operated streetcars in the city, it proposed that VER&LCo build the section from Carrall Street to Cedar Cottage, including the Park Drive stretch. The streetcar company gained the right to operate a city service on that part of the line, but that was a grant it took more than a decade to fulifill.iii

Just a few months later, in the fall of 1891, the first tramcar to make a through trip from Vancouver to New Westminster carried Vancouver Mayor David Oppenheimer, the CPR’s William Van Horne, and Lords Mount Stephen and Elphinstone. As the backers of the interurban and the buyers of speculative lots had hoped, the inauguration of the electric railway was the spur to a steady, if not spectacular, increase in the number of households along the route. Within a month the interurban was making two scheduled round trips each day at a fare of 50c one way or 75c return, the Grandview area being serviced from a stop at Largen’s Corner — the modern Venables and Glen intersection — and soon the earliest pioneers were joined by a few neighbors.iv

[credit: BC Hydro from Ewert 1986, p.26]

In an interview in the 1930s, H.P. Craney told Major Matthews that there “were three houses only between the two cities of New Westminster and Vancouver when the first interurban street railway first operated.” Engineer Scoullar thought that was too low a number, but they agreed there was no density of population anywhere between the two urban areas. There was, however, a strong market for the service. “The demand for seats or even standing room on the inter-city electric tram cars is about 200% in advance of present supply,” claimed the NewsAvertiser during that first week, and extra trains were added by week’s end.v

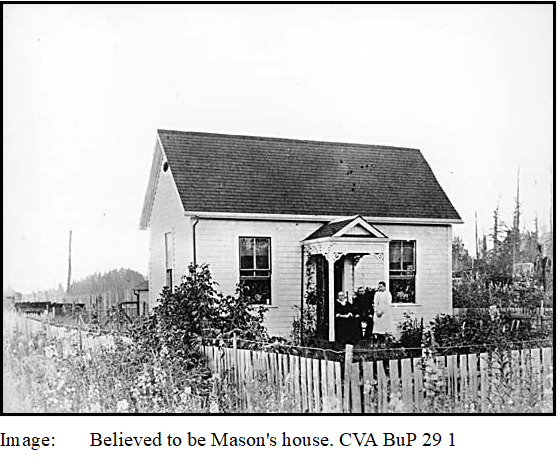

In that same summer of 1891, John Mason became the first resident of the Drive area. He was 35 years old, an immigrant from Scotland. His wife Martha, originally from Nova Scotia and of Irish background, was 47. In the Census that summer, Mason had listed himself as an unemployed farmer. However, soon after, he was hired as a fireman at the newly-opened BC Sugar factory. This new security presumably allowed him to buy three lots and to hire Leonard Sankey and Harry Langdale as contractors for his house. Under Mason’s instructions, the contractors built the first house in Grandview at what would later be designated 1617 Graveley Street but which was then just a clearing off a logger’s ‘snake-out’ path. Noting that Park Drive was still uncleared, Leonard Sankey said “we went to the house by a skid road, and we had to carry the lumber” up the hill from False Creek.vi

What Mason paid for was a plain and simple single-storey two room house. Holdsworth wrote that

“ such small cottages and cabins were common. One storey high, one room deep and balanced symmetrically around a central doorway, they presented a folk classicism as elegant as more expensive structures elsewhere in the city. The surroundings may have been chaotic, but the disorder of stumps testified to clearing done.”

In later years Mason would extend the building to the rear, creating a kitchen and adding plumbing, but for now it was adequate if a little cramped. The landscaping — an ocean of freshly cut stumps cleared by the road gang laying the interurban tracks — left a lot to be desired but it was, after all, evidence of the approach of civilization. One of John Mason’s workmates from the sugar refinery used to visit him during those years. He would bring along his wife and his young daughter. Many years later, Daisy May could vividly recall her mother’s long dress becoming snagged as they climbed over the stumps and fallen logs in their path. She remembered that the hills were “still thickly wooded”, and that bear, cougar and deer still roamed through the bush south of False Creek. These trips were quite the adventure for a young girl.vii

It is impossible to discover now, more than a hundred and thirty years later, what motivations drove John Mason to buy the lots and build where he did, well away from the downtown subdivisions. Was he consciously staking a claim in what he expected to become a thriving neighbourhood? Was it because he could walk down to work on the Inlet? Or was it just that the land and materials were cheaply acquired and therefore attractive to a factory worker? Whatever the reason, John Mason and his family would be only the first of very many working people to find a home in Grandview. Over the next few years, in the 1890s, a few enterprising souls cleared a few more lots near the park trail, built a house or a shack, and became neighbours to the Mason family.

For example, an unknown speculator built a three-room house with a cedar shake kitchen lean-to on a lot north east of the Masons at 1732 Kitchener: the lot and house together were offered for sale at $375, with one hundred down and the balance on small monthly payments. Charles Burns, who had been the foreman at the Royal City Planing Mills on Carrall Street until, when the owners reduced wages for all hands in the early 1890s, he had quit in disgust. He and his wife Muriel began renting rooms on Barnard Street for sixteen dollars a month, but as the months passed by and all Burns could find was the occasional odd job, the offer of a Grandview house at low cost became attractive. Charles Burns made the commitment, purchasing the property in 1892 or 1893.

Burns’ wife, one of those strong, self-sufficient women without whom the conquest of the West would have been quite impossible, made the best of it all. Although noting that “where Kitchener Street is now there were great big logs, three, four, or five feet through — dozens of them — lying all over the place, crossways on top of each other in heaps,” this became a virtue because “our fuel cost nothing, but to saw the logs”. And although there was no electricity or sewer, they had a wonderful well supplying “beautiful water: clear, pure and cold”. They also kept a cow that was forever wandering onto the streetcar tracks, forcing the interurban to stop while the engineer tried coaxing or pulling the animal away.

Mabel Burns remembered the fire that destroyed her home in 1897.

“At the time our home burned, Grace, our fourth child, was about a year old, and it was a Saturday morning, and the three children were playing outside, and it had been a very dry summer, and lots of fires around, there was a lot of burning in the clearing going on then, and there was only a stove pipe chimney in our cedar shake lean-to kitchen, and I had started the fire to get lunch ready, and I heard some crackling above me on the roof, so I went out, and here was the smoke curling up from the roof. I got a bucket of water, and a dipper, and I got a ladder and climbed up, but had not the strength to put it out; I was too weak. Mr. Cronk lived close by, and there was a long log which ran over to his place, which we used to walk along the log to go there, and I told Willie to go over and tell him, but I could not get that boy to go; he kept on calling, ‘Come out, come out, Mother, come out, Mother, you’ll get burned,’ but finally he went, and Mr. Cronk came but it was too late; the fire was too far gone.

“The fire cleaned up about everything; all we had left was taken to town in an express wagon. It was noon, and they stopped the passing interurban car, and the passengers all got out, and helped to pack stuff out of the house.”viii

Other pioneering settlers included B.M. Cronk, the carpenter mentioned above, at the eastern corner of Grant and Commercial, and the Mr. Grant himself, after whom the street would eventually be named. This enterprising new resident maintained a large sign reading “GRANT” by the side of the tramway so that his freight could be dropped off at the right place. Major James Matthews — later Vancouver’s Archivist — remembered seeing the black-painted board nailed to a stump, when he and other cadets marched through the area on their way to drill around the turn of the century. Muriel Burns also recalled an elderly music teacher named Smith, who lived with a “frail looking husband, tall and dark” in a house near where Grant joins Victoria. Mrs. Smith would come over to Muriel’s place and “stay for a while… when it was cold in the morning.” Of the other earliest pioneers of the Drive — regular working folks like George Williams, a labourer, and the two Hastings Mill’s employees, Franklin Shunn and Joseph Hamilton — little more is known than their names in a bare directory listing.ix

Population growth was not of immediate concern to the speculators who owned most of the land in and around Grandview in those years. However, by the end of this period, huge landowners, such as the Oppenheimers and Duponts, began to break up their estates to capitalize on their investments. By 1889, agents such as R.G. Tatlow & Co, and Green & Birchall could offer $125 an acre for entire blocks on Park Drive between what would become Bismark Street and First Avenue, and another at 3rd & Park, and lots “on the Tramway line” for $120”.x Ross & Ceperley said “$3,000 will buy a cleared block of 24 lots in Sub 264a, near the NW & V Electric Line. Terms – One third cash, balance in 6 and 12 months. A large number of fruit trees are planted, and 1,000 strawberries are set. Three of the lots are graded.”

But as good as that sounded, there was no rush in the 1890s to take up those lands. There are a great many indications that real estate and economic activity of the 1890s and early 1900s generally had by-passed Grandview: A future mayor of Vancouver could legitimately claim that, in 1901, there was still “no such place” as Grandview; Charles Goad, the urban cartographer, found nothing to map in Grandview in 1897, 1901 or 1903; in July 1903, the City Engineer submitted his report on sewer additions required for the following year. The furthest east mentioned was Vernon Street; in the Chief of Police’s plan to introduce patrol box telephones in every district during 1904, none of the “Beats” include Grandview or anything close by; the City Directories list no streets in Grandview in 1901 and 1902. It is not until 1903 that a few streets are mentioned. In a major front page article in the spring of 1904 entitled “Great Activity in Real Estate” describing the rush to build in Vancouver as the year progresses, the Vancouver World doesn’t mention Grandview at all. And as late as the end of March in that year, Ald. Garrett could still argue that “streets should not be opened away in the bush when so much work still had to be done right in the City.”xi

The fact is, that by 1901, according to the Canadian Census of that year, Grandview had grown to be home to just 24 households, with 110 people, of whom 54 were adults (32 men, 22 women) and 56 children (31 boys, 25 girls). Many of them lived in the Cedar Cove neighbourhood and elsewhere across Grandview, but it includes John Mason along with Frederick Bridge, a labourer living at Grant & Park, two Odlum households, M. Raine who lived at Park & First, Isaac Russell, a carpenter also living at Park & Grant, and their families.xii

They had the Park trail, the interurban tracks, their neighbours, and themselves. Could that be enough to build a community?

i “a strong suspicion”: George F. Gibson interview with Matthews, CVA Add MSS 54.013.06209. See also Conn & Ewart 2003, p.32

ii For the origins of the park trail see: https://grandviewheritagegroup.ca/2022/09/16/the-drive-in-the-beginning/ and https://grandviewheritagegroup.ca/2022/04/19/grandviews-parks-to-1930/. The best general account of the development of the electric railway is Henry Ewart The Story of the BC Electric Railway 1986 qv MacDonald 1992, p.26-27. Matthews interviews with W.D. Burdis and H.P. McCraney, CVA Add MSS 54.013.06209, are also interesting in this regard, as is his interview with Capt. Scoullar in Vol I, p.177-178. Engineering surveys: The Truth quoted in Vancouver World, 1890 July 29, p.4; approved route: Ewart 1986, p.19-20.

iii Ewert 1986, p.19-20

iv The final weeks and days of construction are covered well in Vancouver Daily World 1891 Aug 13, p.8; Oct 3, p.8; Daily News Advertizer 1881 Oct 1, p.8; 10, p.5

v H.P. Craney in Matthews 2010, Vol I, p.72; Capt Schouler Vol I. p.177-178. “200%” in Daily News Advertizer 1891 Oct 24, p.6; 27, p.6

vi L.T. Sankey interview in Matthews, CVA AM54,.013.03120

vii Holdsworth 1986, p.15. Daisy May Peachey’s reminiscences are from Sun 1972 Nov 14, p. 71

viii Mrs Burns gave a wonderfully full account to Major Matthews in 1944 Vol IV, p.80-84

ix Cronk, Smith, Williams, Shunn and Hamilton are from “Williams Directory of BC, 1894”; more information on Cronk and Smith can be found in CVA Add MSS 54.013.01816.

x For a huge sale by Major C.T. Dupont see Vancouver Daily World 1889 Jul 23, p.1. R.G. Tatlow & Co ad in Vancouver Daily World 2 Jan 1889, p.2, and often thereafter. Green & Birchall: Vancouver Daily World 1891, Aug 2, p.1. Ross & Ceperley: Vancouver Daily World 1891 Aug 8, p.3

xi “no such place”: Thomas Neeland interview with Matthews, Vol 5, p.119; see Goad’s maps in the National Archives Online collection; engineer’s report: Vancouver World 1903 Jul 8, p.5; police beats: Vancouver World 1904 Mar 15, p.4; Vancouver City Directories, 1890-1903; real estate: Vancouver World 1904 Mar 4, p.1; Alderman Garrett: News Advertiser 1904 Mar 25, p.5, April 1, p.11.

xii 1901 Canadian Census; City Directories 1900-1903